TRACE FOSSILS

Trace fossils are any indirect evidence of ancient

life. They refer to features not representing parts of the body of a

once-living organism. Traces include footprints, tracks, trails, burrows,

borings, and bitemarks. Body fossils provide information about the

morphology of ancient organisms, while trace fossils provide info. about the behavior

of ancient life forms. Interpreting trace fossils and determining the

identity of a trace maker can be straightforward (for example, a dinosaur footprint

represents walking behavior) or not. Sediments that have trace fossils

are said to be bioturbated. Burrowed textures in sedimentary rocks

are referred to as bioturbation. Trace fossils have scientific

names assigned to them, in the same style & manner as living organisms or

body fossils.

Skolithos linearis

Skolithos linearis (Haldeman, 1840) burrows in quartzose sandstone (9.0

cm across at its widest) from the Antietam Formation (Upper Cambrian) in the

Antietam area, NE of the Potomac River, southern Washington County, western

Maryland, USA.

Many shallow-water quartzose sandstones have

conspicuous, long, vertical burrows called Skolithos linearis.

Geologists traditionally consider Skolithos as a burrow of a

filter-feeding vermiform organism in a shallow-water, high-energy

lithofacies. Most Skolithos occurrences in the geologic record may

be safely interpreted as such, but some demonstrably terrestrial examples

constructed by other organisms have been recently discovered (e.g., see Martin,

2006).

Skolithos linearis burrows (cross-section view; lens-cap for scale) in

quartzite (well-cemented quartzose sandstone), Clinch Quartzite, Lower

Silurian; Clinch Mountain, Tennessee, USA.

Skolithos linearis burrows (plan view - small circular structures; lens

cap for scale) in quartzite (well-cemented quartzose sandstone), Clinch

Quartzite, Lower Silurian; Clinch Mountain, Tennessee, USA.

FOSSIL BIRD TRACK

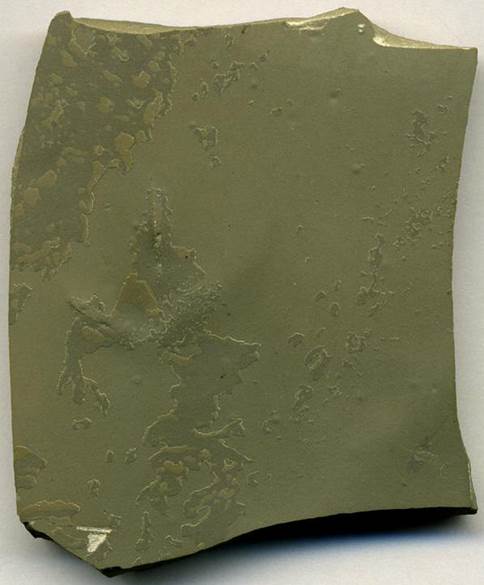

Fossil bird footprint (above & below; rock is 5.2 cm across) impressed

on grayish-green argillaceous lime mudstone (below: sole of above slab

showing underprint/undertrack). This comes from Utah's famous Soldier

Summit Fossil Track Horizon. A persistent horizon of intensely

bioturbated argillaceous lime mudstone occurs in the Eocene-aged Green River

Formation near Soldier Summit (southern Wasatch County, north-central Utah,

USA). This area was once the southwestern shore of ancient Lake Uinta.

This print was made by some wading bird, probably something like a sandpiper

(see Moussa, 1968).

DINOSAUR TRACKS

Anchisauripus exsertus (Lull, 1904) (left) theropod dinosaur

footprint from the Connecticut River Valley of eastern America (CMC public

display - Cincinnati Museum of Natural History & Science, Cincinnati, Ohio,

USA).

Eubrontes giganteus Hitchcock, 1845 (right) theropod dinosaur

track (~30-35 cm across at its widest) in fine-grained sandstone of the

Longmeadow Formation (Upper Triassic/Lower Jurassic), Mt. Tom Dinosaur

Tracksite, north of Holyoke, Connecticut River Valley of Massachusetts, USA.

Apatosaurus footprint (reproduction) from the Upper Jurassic of western America

(public display, Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago, Illinois, USA).

Dinosaur tracksite - dinosaur-trampled sediment surfaces are referred to

as dinoturbation. At the locality shown here, 325 dinosaur tracks

made by 37 individuals are impressed on quartzose sandstones.

Stratigraphy: Dakota Sandstone, upper Lower Cretaceous.

Locality:

eastern side of Dinosaur Ridge, Colorado, USA.

Diplocraterion

Diplocraterion in calcisiltite from the Arnheim Formation (lower

Richmondian Stage, upper Cincinnatian Series, upper Upper Ordovician) of

southwestern Hamilton County, Ohio, USA. This is a bedding plane view of

a Diplocraterion U-tube (apparently D. helmerseni or D.

biclavatum). MUGM 8099 (Karl E. Limper Geology Museum,

Miami University, Oxford, Ohio, USA).

Diplocraterion is a distinctive U-tube shaped trace fossil (see

cross-section view). In bedding plane view, it is often a

dumbbell-shaped structure. It is moderately common in the Upper

Ordovician fossiliferous limestone-shale succession of southwestern Ohio,

southeastern Indiana, and northern Kentucky (the Cincinnatian Series).

U-tubes having parallel sides have been called Diplocraterion parallelum.

U-tubes having a flared base have been called Diplocraterion helmerseni.

Specimens having a pair of blind pouches at the bottom of the U-tube have been

called Diplocraterion biclavatum.

Asteriacites

Asteriacites on underside of very fine-grained quartzose sandstone (rock is 7.0 cm

across), unrecorded Pennsylvanian-aged stratigraphic unit from an undisclosed

locality in Kansas, USA.

Asteriacites is one of the most distinctive invertebrate trace fossils

around. Asteriacites is a burrow made by a starfish

(Phylum Echinodermata, Class Asteroidea) or brittle

star (Phylum Echinodermata, Class Ophiuroidea). The specimen shown

here is a convex hyporelief on the underside of a very fine-grained sandstone

from Kansas. Fine striations along the impressions of the arms represent

digging motions by the tube feet. Even the depression in the mouth area

shows scratches (not really visible in this photo) made by movements of the

mouth frame.

Fustiglyphus annulatus

Fustiglyphus annulatus specimen from the Arnheim Formation (lower

Richmondian Stage, upper Cincinnatian Series, upper Upper Ordovician) at Lanes

Mills, Oxford, southwestern Ohio, USA. MUGM 8098 (Limper Geology Museum,

Miami University, Oxford, Ohio, USA).

One of the stranger trace fossils described in the

literature is Fustiglyphus (often misidentified as Rhabdoglyphus).

It's a relatively narrow, parallel-sided burrow with significant swellings at

semi-regular intervals.

Making sense of this burrow type has been difficult

(see Osgood, 1970). The burrow is inferred to be entirely infaunal,

despite its common presence at weathered-out bedding planes. The Fustiglyphus

maker appears to have preferred burrowing at sediment interfaces (silt-mud

interfaces, sand-mud interfaces, etc.). What specific behavior generated

the swellings is unclear. The modern snail Illyanassa has been

observed occasionally excavating a shallow depression along its locomotion

trails, but those are epifaunal traces.

CROCODILIAN CLAW SCRATCH MARKS

Crocodilian claw scratch marks in the Dakota Sandstone (upper Lower Cretaceous),

eastern Dinosaur Ridge, Colorado, USA.

DEVIL'S CORKSCREW

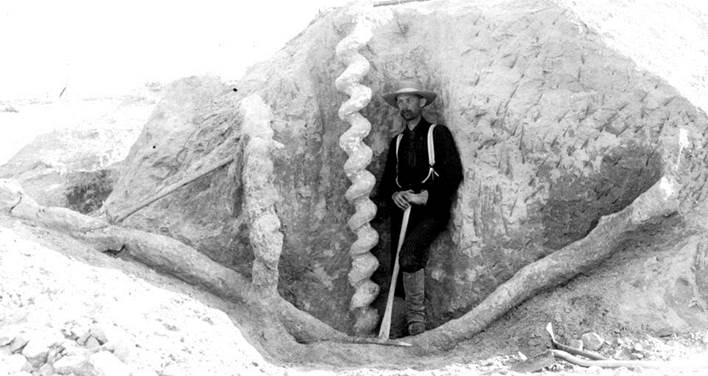

Daemonelix burrows (above & below) - “Devil’s corkscrews” from a paleosol in

the Harrison Formation (upper Middle Miocene) in Sioux County, northwestern

Nebraska, USA.

This distinctive spiral burrow was made by an ancient

species of terrestrial beaver. The spiraled portion of these trace

fossils is usually about 1.5 to 2 meters tall. The base of the spiraled

portion merges with a subhorizontal tube. The burrow filled with

siliciclastic sediments that was better cemented compared with surrounding

materials.

Above:

reproduction on public display, Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago,

Illinois, USA.

Below:

vintage field photo of excavated Daemonelix

burrows in a Harrison Formation paleosol in what is now Agate Fossil Beds

National Monument (original photo: University of Nebraska; photo provided here

courtesy of Agate Fossil Beds National Monument).

Some references:

Moussa (1968) - Journal of Paleontology 42(6):

1433-1438.

Osgood (1970) - Trace fossils of the Cincinnati

area. Palaeontographica Americana 6(41): 369-371, 433, pl. 78.

Häntzschel (1975) - Trace fossils and

problematica. Treatise on Invertebrate Paleontology, Part W,

Miscellanea, Supplement 1. pp. 63, 64, 98-101.

Stanley & Pickerill (1998) - Systematic ichnology

of the Late Ordovician Georgian Bay Formation of southern Ontario, eastern

Canada. Royal Ontario Museum Life Sciences Contributions

162. 55 pp.

Martin (2006) - Trace Fossils of San Salvador.

San Salvador, Bahamas. Gerace Research Center. 80 pp.