GASTROPODS

The gastropods (snails & slugs) are a group of

molluscs that occupy marine, freshwater, and terrestrial environments.

Most gastropods have a calcareous external shell (the snails). Some lack

a shell completely, or have reduced internal shells (the slugs & sea slugs

& pteropods). Most members of the Gastropoda are marine (see modern

examples below). Most marine snails are herbivores (algae grazers) or

predators/carnivores.

CONIDS

The conid gastropods (cone shells) are fascinating marine

snails for a couple reasons - they have attractively-shaped, colorful shells

and they are killers. The conids are predatory, as are many other

marine snails, but they take down their prey in an unusual fashion. The radula

of most snails is a mineralized or heavily sclerotized mass of small teeth that

scrapes across a substrate during feeding. Conid snails have a toxoglossate

radula - one that has been evolutionarily modified into tiny, unattached,

toxin-bearing, harpoon-like darts (see

photo) that can be fired at prey. Each dart is an individual

tooth. The nickname "killer snails" is well deserved (even

people have been killed). Some species have incredibly powerful toxins,

while in other species the toxin has little effect on humans.

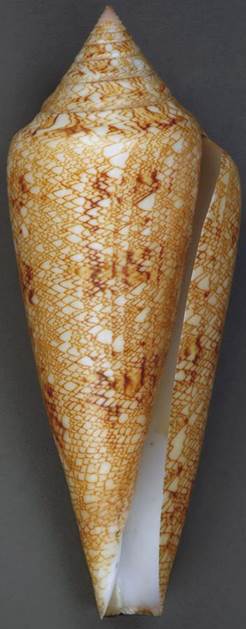

Conus gloriamaris (7.8 cm tall) - abapertural (left) and

apertural (right) views. The apertural edge has not been filed (unlike

many snail shells in the retail shell market) & the protoconch is present.

The conid shell shown above & below is one of the

most famous rare seashells in history - Conus gloriamaris, the

glory-of-the-seas cone. Conus gloriamaris (a.k.a. Conus

(Regiconus) gloriamaris; a.k.a. Cylindrus gloriamaris; a.k.a.

Conus (Cylindrus) gloriamaris; a.k.a. Cylindrus (Regiconus)

gloriamaris) is a modern, tropical marine gastropod. The hard shell,

or conch, has a distinctively elongated, gently tapering shape and a more sharply

tapered top. This species’ shell surface coloration consists of a medium

to dark brown colored “tent” pattern on a pale creamy yellow background (many

conid gastropod shells have broadly similar tent patterns). Individual

tents vary in size.

Conus gloriamaris was first named & described by Johann Chemnitz in

1777. Shell collectors treasured specimens of this species, which

remained very rare from the time of its original description up to the late

1960s. Conus gloriamaris is not an abundant species, but shells

are now available in the retail market.

Classification: Animalia, Mollusca, Gatropoda, Neogastropoda,

Conoidea, Conidae

Natural distribution: intertidal to <100 meters depth, western Pacific

Basin.

Conus gloriamaris - apical portion of conch (left) and apical view of

conch (right, ~2.5 cm across) showing dextral coiling. Dextrality is an

almost universal trait in conchiferous gastropods. Only rarely can

counter-clockwise coiled shells be found (left-handed coiling/sinistral

coiling).

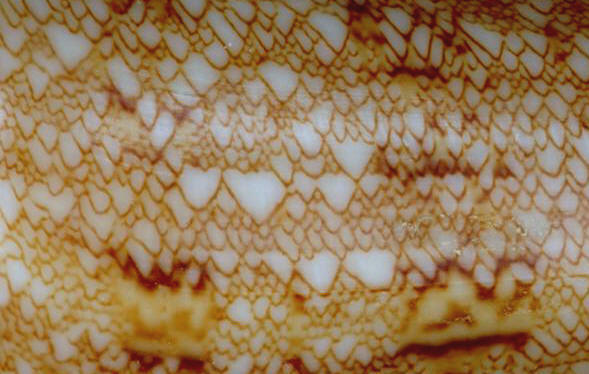

Conus gloriarmaris - conch surface showing tent pattern (field of view

~2.7 cm across).

FICIDS

Here’s a graceful fig shell (a.k.a. elongated

fig shell), Ficus gracilis (see

photo of snail inside this shell). This is a modern, predatory, tropical

marine gastropod from the western Pacific Basin that inhabits unconsolidated

sand substrates and preys on irregular echinoids. The shell itself is

relatively thin & lightweight.

Classification: Animalia, Mollusca, Gastropoda, Neogastropoda, Ficoidea,

Ficidae

Ficus gracilis shell - abapertural (left) and apertural (right)

views (10.3 cm tall). The apertural lip has been filed (this is commonly

done to retail specimens).

COSTELLARIIDS

The colorful queen vexillum shell (Vexillum regina)

is spectacularly colored with white, orange, and dark brown stripes (the

species does vary in coloration, however). It is a modern, tropical

marine gastropod from the western Pacific Basin. Vexillum is a

predatory snail that secretes toxins to immobilize & kill prey.

Classification: Animalia, Mollusca, Gatropoda, Neogastropoda,

Volutoidea, Costellariidae

Vexillum regina shell (6.2 cm tall) - abapertural (left) and

apertural (right) views.

WORM SNAILS

Here’s one of the more bizarre gastropod shells

around. This is Vermicularia, also called a worm snail. It’s

one of the few snails that does not have a tightly coiled shell. Several

snails from different families have shells somewhat like this (e.g., the

vermetids & the turritellids). They all resemble the twisted

mineralized shells made by some annelid worms, hence the common name “worm

snails” or “worm shells”.

Despite the superficially very different-looking

shells, malacologists have demonstrated that Vermicularia is very

closely related to the high-spired snail Turritella.

Juvenile Vermicularia are free living, infaunal filter feeders that

position themselves apex-down and aperture-up within the sediment. During

this stage in ontogeny, the Vermicularia shell is tightly coiled, as is

any ordinary gastropod shell. Later in life, the snail becomes an

epifaunal, encrusting filter feeder (assuming hard or firm substrates are

available), and its shell starts uncoiling. The advantage of an uncoiled

shell in Vermicularia is generally inferred to be rapid upright growth

(that’s desirable for a sessile, benthic filter feeder).

If hard or firm substrates aren’t available, Vermicularia

generally doesn’t grows an unwound shell during growth, and they end up looking

like typical Turritella shells. The degree of uncoiling also

depends on the nature of the hard substrate (e.g., a ramose scleractinian coral

vs. a hemispherical scleractinian coral vs. a bivalve shell). So, shell

uncoiling is an ecophenotypic character.

Classification: Animalia, Mollusca, Gastropoda, Mesogastropoda,

Cerithioidea, Turritellidae

Vermicularia (worm snail) (9 cm tall)

Most info. synthesized from Morton (1953) and Gould

(1968, 1969):

Morton (1953) - Vermicularia and the

turritellids. Proceedings of the Malacological Society of London

30: 80-86.

Gould (1968) - Phenotypic reversion to ancestral form

and habit in a marine snail. Nature 220: 804.

Gould (1969) - Ecology and functional significance of

uncoiling in Vermicularia spirata: an essay on gastropod form. Bulletin

of Marine Science 19: 432-445.

XENOPHORIDS

The xenophorid snails (a.k.a. carrier snails),

especially members of the genus Xenophora, are remarkable in

their tendency to pick up other shells, skeletal fragments, rock fragments, or

corals (sometimes still alive) from their surrounding environment and cement

these objects to their own shells. The result looks like a pile of shells

on the seafloor. Often, sponges and serpulid worm tubes are found

encrusting the xenophorid shell - they contribute to the illusion that a

xenophorid is simply a patch of seafloor. Xenophora carrier shell

snails do this as a camouflage defense against predators. Decorator

crabs are arthropods that do this as well.

Xenophorids are principally detritivores on

unconsolidated, fine-grained to coarse-grained to rubble-bottom substrates.

Classification: Animalia, Mollusca, Gastropoda, Mesogastropoda,

Xenophoroidea, Xenophoridae

Xenophora carrier shell (above & below; 12.7 cm across; above: apical

view; below: umbilical view) with numerous attached shells. Most

of the objects that have been picked up by this individual are snail shells,

but there are also a few clam shells, and a long worm tube.

Some info. from Harasewych & Alcosser (1991) and

Hill (1996).

MURICIDS

Many muricid snails have highly spinose shells.

The high degree of spinosity in such snails is usually considered an anti-predation

feature. Spinose muricids typically have three axially-oriented rows of

spines per whorl, so that each spine row is ~120º from the next.

Conchologists have pointed out that such spine row distributions provide

orientation stability to the snail and prevent sinking on unconsolidated,

fine-grained, high-water-content sediment substrates. Another suggestion

holds that well-developed spine arrays could act as traps for potential

prey. Muricids are predatory gastropods, but they principally prey

on encrusting, conchiferous organisms (e.g., bivalves, barnacles) by boring

through the shells. It's more likely that the spine arrays protect the

snail from predatory arthropods or fish while engaged in boring & feeding

on prey.

Classification: Animalia, Mollusca, Gastropoda, Neogastropoda,

Muricoidea, Muricidae

Murex pecten Lightfoot, 1786 shell (12.8 cm tall) - abapertural view (left) &

apertural view (right).

Murex troscheli Lischke, 1868 shell (11.8 cm tall) - abapertural view

(left) & apertural view (right).

Some info. from Morris & Clench (1975), Paul

(1981), Harasewych & Alcosser (1991), and Hill (1996).

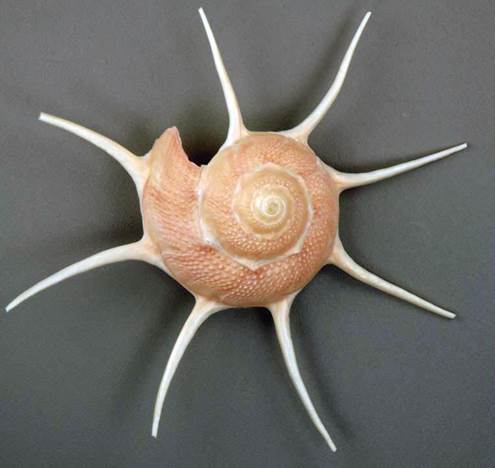

TURBINIDS

The turbinids are common, tropical, herbivorous

snails. One of the more visually intriguing turbinids is the star

turban. This snail tends to inhabit unconsolidated, fine-grained

substrates in moderately deep, low-energy settings. The long spines

projecting from the final whorl's keel are throught to help prevent the snail

from sinking (a common problem among epifaunal, benthic invertebrates

throughout geologic history) and to help prevent predators from easily flipping

the shell over.

Classification: Animalia, Mollusca, Gastropoda, Archaeogastropoda,

Trochoidea, Turbinidae

Guildfordia yoka Jousseaume, 1888 shell (above & below; 8.3 cm

across)

Above:

apical view. Below: umbilical

view.

Some info. from Morris & Clench (1975), Harasewych

& Alcosser (1991), and Hill (1996).

LAMBIDS

The spider conchs, or lambid snails (often grouped

with the true conchs - the strombids), are herbivorous gastropods in tropical

photic zone environments, feeding on benthic filamentous algae. Lambids

can have large, thick shells that are often quite colorful, especially in the

apertural areas.

Classification: Animalia, Mollusca, Gastropoda, Caenogastropoda,

Stromboidea, Lambidae (or Strombidae)

Lambis chiragra (Linnaeus, 1758) shell (the chiragra spider conch)

(22.5 cm tall) - abapertural view (above).

Lambis chiragra shell - apertural view (above). Note the large,

rounded drill hole (1.3 cm diameter) near the left margin of the shell.

The boring hasn’t penetrated through the thick shell wall - evidence for an

unsuccessful predation event.

Lambis scorpio (Linnaeus, 1758) shell (the scorpion spider conch)

(13.5 cm tall) - abapertural view (left) & apertural view (right).

Some info. from Harasewych & Alcosser (1991) and

Hill (1996).